Proposed decree: EIA screening transferred to higher government

Local authorities face a dilemma: they want to invest in public construction projects, but are no longer allowed to assess their own projects when these have a significant impact on the environment. A new draft decree aims to break the deadlock, but at the same time raises questions about how independent the assessment will really be when it is simply shifted to another political level.

From ‘judge and jury’ to a more independent assessment

In our previous contribution, we pointed out the fundamental tension that arose when local authorities had to assess their own projects entirely on their own. The Court of Justice (May 8, 2025) and the Constitutional Court (September 18, 2025) have since confirmed that this is contrary to European law: the EIA Directive requires a truly independent assessment of environmental impacts, including in the screening phase.

In concrete terms, this meant that municipalities and provinces could no longer issue permits for their own projects that required a project EIA screening. Construction files for sports halls, schools, or road works were therefore put on hold. The Flemish government temporarily instructed that such applications be submitted to the higher authorities, but this solution had no basis in law and therefore offered no legal certainty.

What is being proposed?

The draft decree cites several ways out of the impasse. One of these is to strive for greater (actual) independence for the environmental officer. However, this means that this officer must have his own resources and staff, which, according to the proposers of the draft decree, would be unfeasible. Another option is to set up an independent center of expertise for EIA screenings. However, such a center cannot be established overnight and therefore does not offer a short-term solution.

The draft decree therefore opts to transfer the assessment of project EIA screening to the higher level of government. For municipal projects, this is the provincial deputation, and for provincial projects, it is the Flemish government. This creates a legal basis (and permanence) for the interim solution currently in place, with the nuance that further processing and decision-making on the permit remains with the original authority.

In other words, local authorities remain competent to issue their own permits, but the environmental impact screening will henceforth be assessed by the higher authority. In this way, the autonomy of local authorities is largely preserved, without contravening the applicable law.

Transitional measures and regularization

The draft decree also provides for a scheme for ongoing cases and for permits already issued since October 6, 2022. This is the date of the so-called Wasserij rulingby the Council for Permit Disputes, in which it was ruled for the first time that an environmental official cannot independently decide on the EIA screening of a project submitted by their own municipality.

All current files will be transferred to the (new) competent authority with regard to screening. For permits already issued since October 6, 2022, the Flemish Government will be given the power to develop a regularization scheme so that legally granted permits are not at risk of being declared invalid. It will also be tasked with evaluating within 18 months whether this approach is working and whether structural solutions are possible, for example through an independent center of expertise that carries out screenings.

The proposal is therefore essentially temporary and pragmatic: it aims to restart the granting of permits for public projects without the risk of new annulments.

Conclusion

If the draft decree is approved in its current form, project EIA screening for local government projects will henceforth be assessed by the higher authorities. Although this can be seen as a step in the right direction, we are still waiting for a structural reform that will bring the system into line with European law in a sustainable manner. The announced evaluation within 18 months will be an important benchmark in this regard.

After all, the proposal exposes a deeper problem: the intertwining of political and administrative interests in public construction projects. Simply shifting the assessment of environmental impacts to a higher level of government, where the same political dynamics may play a role, does not fully resolve this fundamental tension.

Please do not hesitate to contact Andersen’s real estate team in Belgium for more information and assistance regarding this draft decree, EIA obligations or planning and environmental law in general.

Matias Osorio Olivera

Counsel

Discover more about this topic?

I am looking for a specialist in

See more articles

07.11.2025

•Urban Planning and Environmental Law

No financial charges may be imposed in an environmental permit without an urban planning regulation.

The Council for Permit Disputes (RvVb) annulled, on 9 October 2025, a financial charge imposed in a decision granting an environmental permit. Such a charge may, since 2024, only be imposed on the basis of an urban planning regulation within the meaning of Articles 2.3.1 and 2.3.2 of the Flemish Code for Spatial Planning (VCRO). Prior to the amendment of the Decree, the Environmental Permit Decree did provide that such a financial charge could be imposed by the permitting authority and under what conditions, but it was not required that a regulation be included in an urban planning ordinance.

04.11.2025

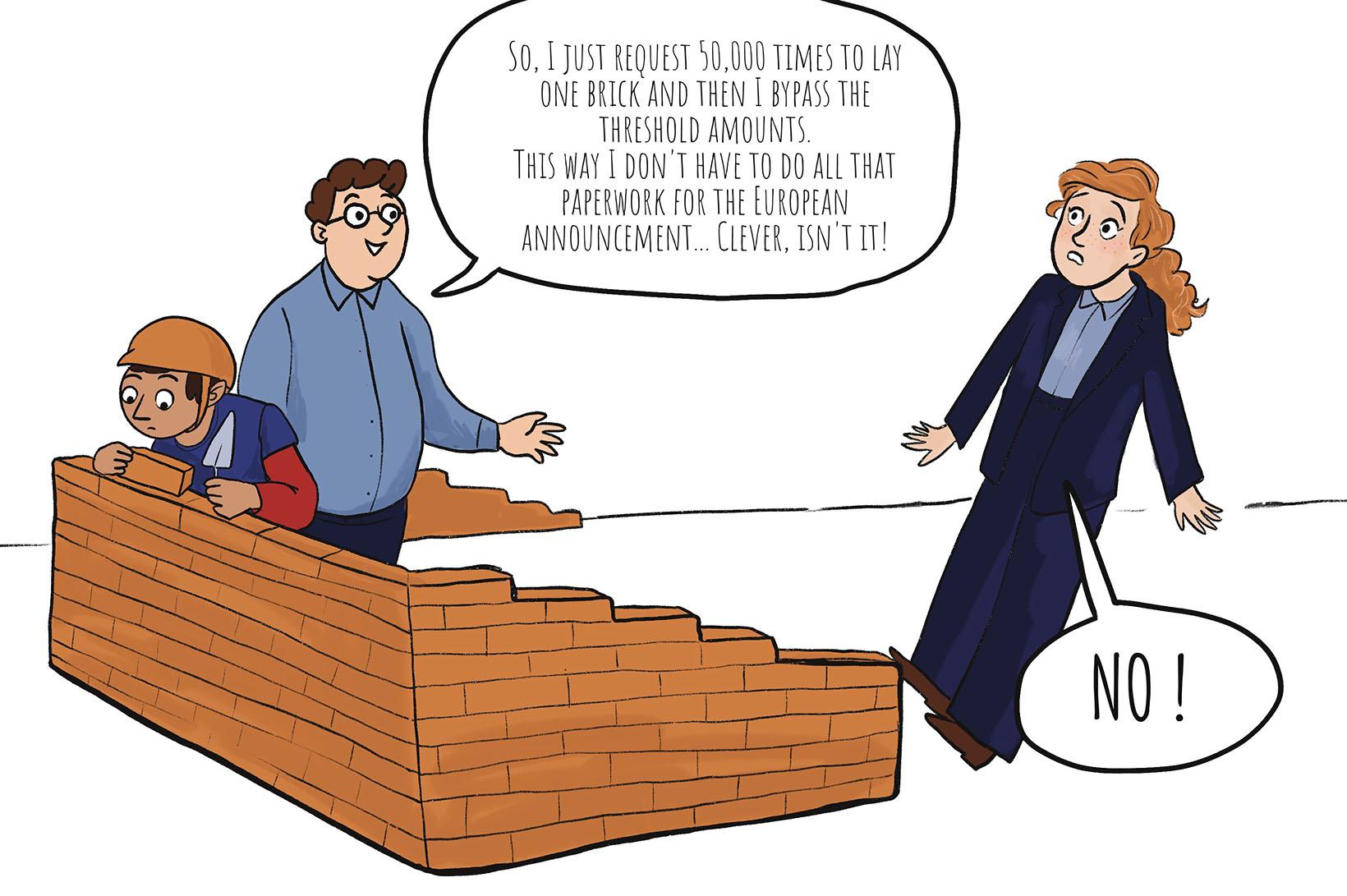

•Administrative Law and Public Procurement

Tightening of public procurement regulations following new European threshold amounts from January 1, 2026

On October 23, 2025, the new European threshold amounts that tighten public procurement regulations were published in the European Official Journal. When awarding public procurements, the contracting authority must take into account a number of threshold amounts.

29.10.2025

•Tax Law

Tax challenges for cryptocurrency investors

What are the potential risks faced by cryptocurrency holders under current tax legislation and in light of the future taxation of capital gains on financial assets?

22.10.2025

•Urban Planning and Environmental Law

Reconstruction of destroyed or damaged non-zoned dwelling: No time pressure without a clear insurance amount

The Council for Permit Disputes (RvVb) recently overturned a decision by the province of East Flanders to refuse an environmental permit for the reconstruction of a burned-down, non-zone-compliant dwelling. The RvVB ruled that the period within which the application for such a permit must be submitted only begins once there is certainty about the amount of insurance granted.